A current topic that is greatly under-reported involves the critical shortage of "rare-earth" minerals. These elements are needed in all facets of technology and are especially important

in all forms of renewable energy. Simply put, this is a crises - a crises in which you have never hear of. For a good overview of the end use of various kinds of rare earth minerals go HERE.

Much of the content of this material draws from two recent and comprehensive reports. Below is the reprinted abstract from

the European Union (EU) point of view:

Due to the rapid growth in demand for certain materials, compounded by political risks associated with

the geographical concentration of the supply of them, a shortage of these materials could be a potential

bottleneck to the deployment of low-carbon energy technologies. In order to assess whether such

shortages could jeopardise the objectives of the EU's Strategic Energy Technology Plan (SET-Plan), an

improved understanding of these risks is vital. In particular, this report examines the use of metals in the

six low-carbon energy technologies of SET-Plan, namely: nuclear, solar, wind, bioenergy, carbon capture

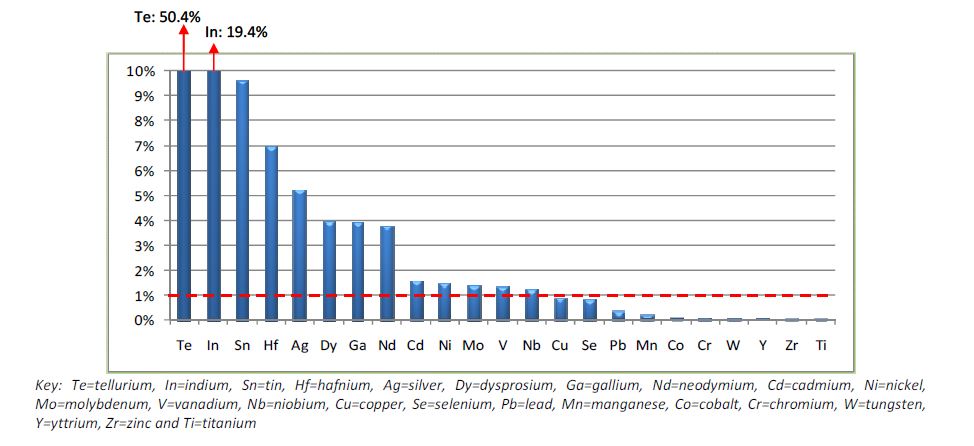

and storage (CCS) and electricity grids. The study looks at the average annual demand for each metal for

the deployment of the technologies in Europe between 2020 and 2030. The demand of each metal is

compared to the respective global production volume in 2010. This ratio (expressed as a percentage)

allows comparing the relative stress that the deployment of the six technologies in Europe is expected to

create on the global supplies for these different metals. The study identifies 14 metals for which the

deployment of the six technologies will require 1% or more (and in some cases, much more) of current

world supply per annum between 2020 and 2030. These 14 metals, in order of decreasing demand, are

tellurium, indium, tin, hafnium, silver, dysprosium, gallium, neodymium, cadmium, nickel, molybdenum,

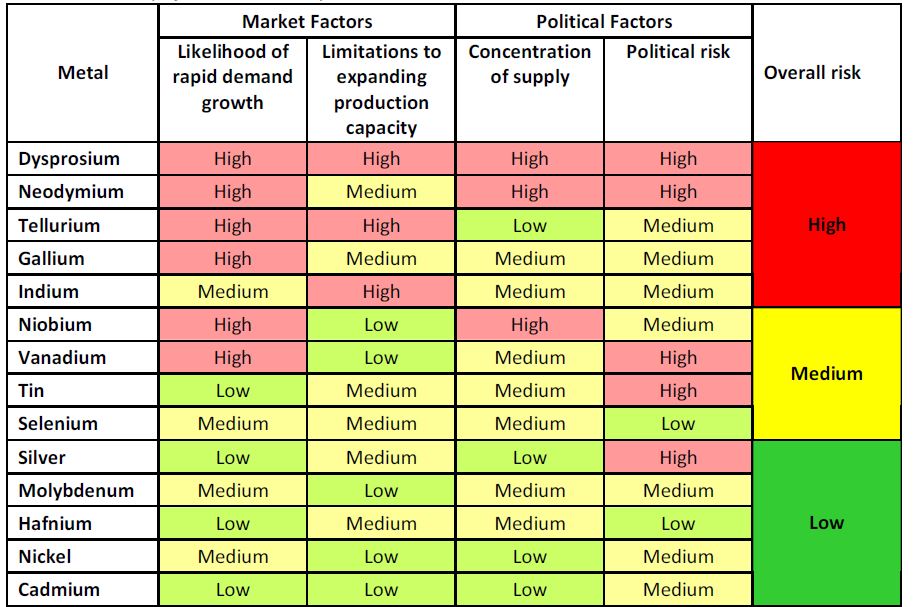

vanadium, niobium and selenium. The metals are examined further in terms of the risks of meeting the

anticipated demand by analysing in detail the likelihood of rapid future global demand growth,

limitations to expanding supply in the short to medium term, and the concentration of supply and

political risks associated with key suppliers. The report pinpoints 5 of the 14 metals to be at high risk,

namely: the rare earth metals neodymium and dysprosium, and the by-products (from the processing of

other metals) indium, tellurium and gallium. The report explores a set of potential mitigation strategies,

ranging from expanding European output, increasing recycling and reuse to reducing waste and finding

substitutes for these metals in their main applications.

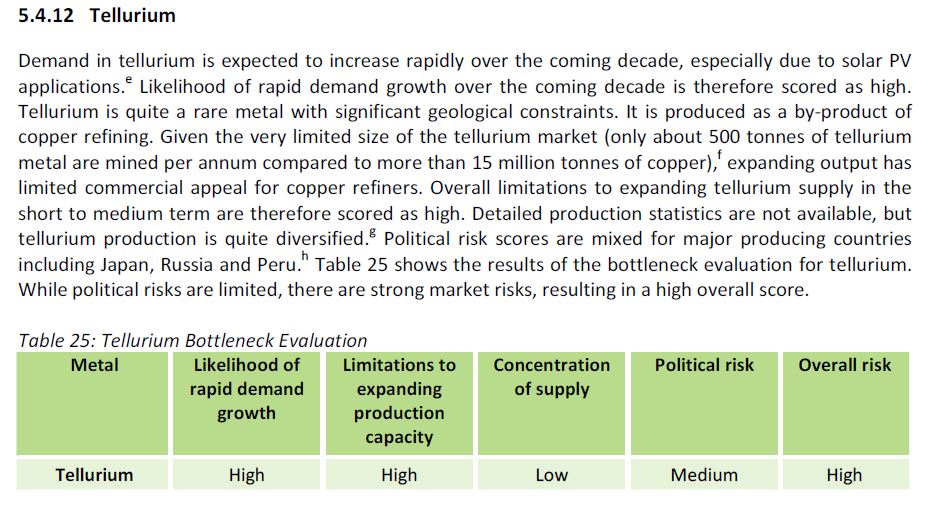

The current situation can be represented by this graph which shows the percentage of 2030 World supply of these rare earth's relative to their demand in just renewable energy systems.

Clearly, the use of Te (Tellurium) will not scale. This is one of the

reasons why First Solar is not scalable since they need Tellurium as their base material.

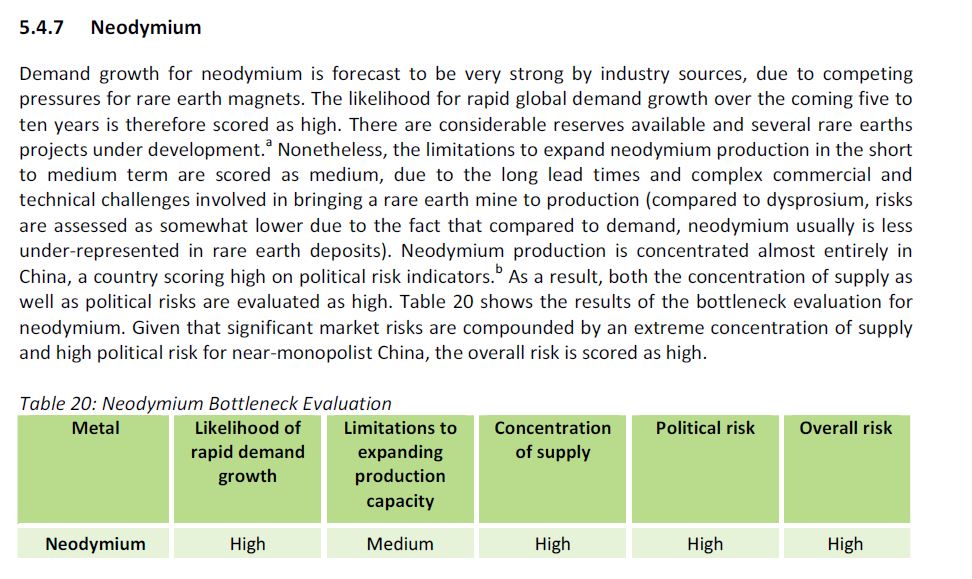

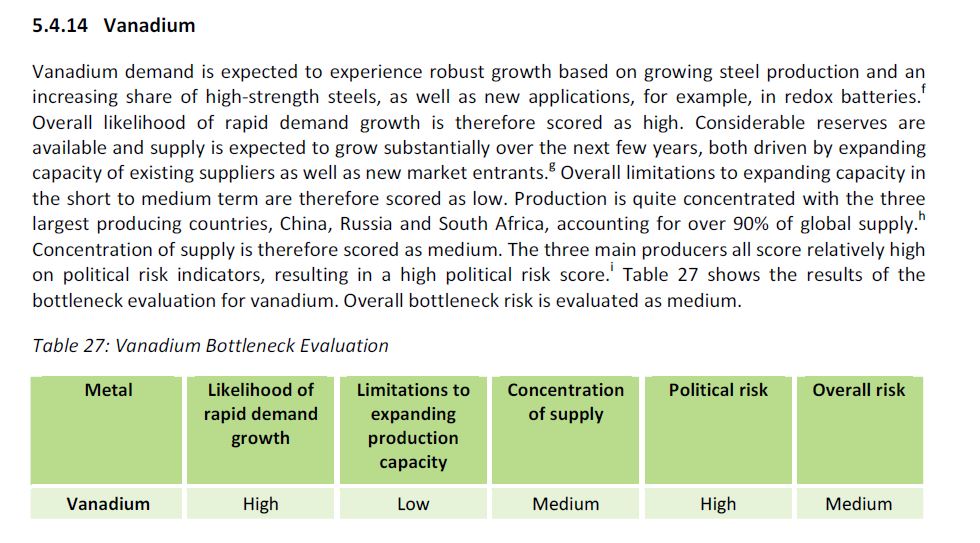

The following table identifies supply chain risks. Note that many of these materials are also used in various medical technologies.

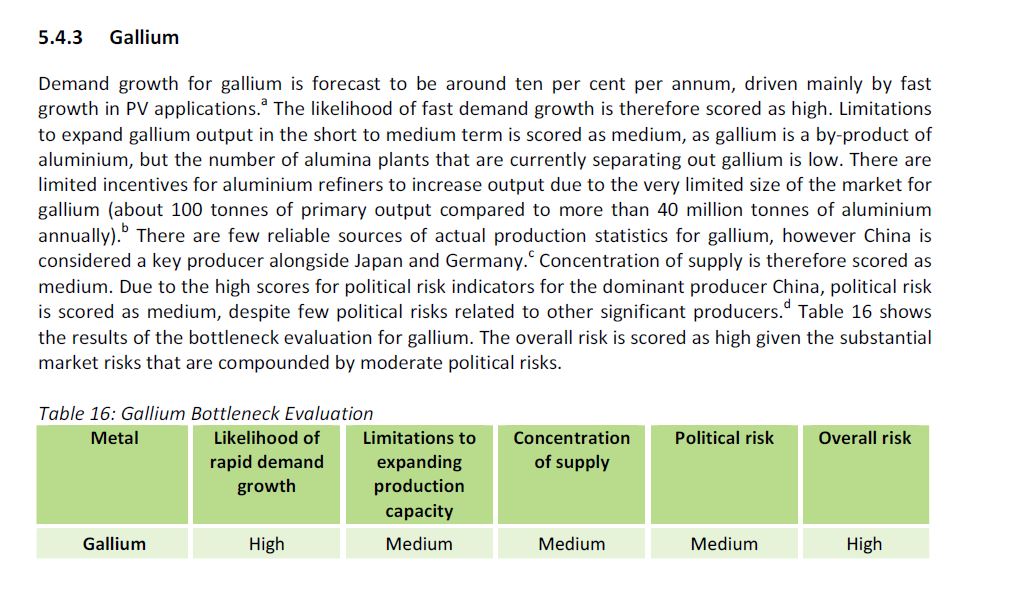

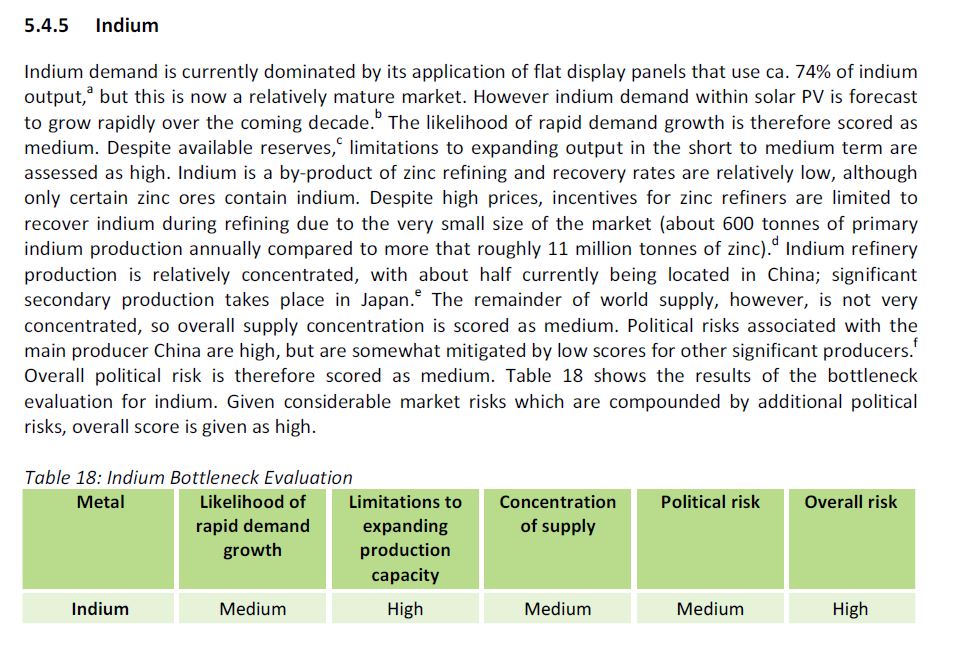

Below are a few details for some of these critical elements with the highest levels of risk:

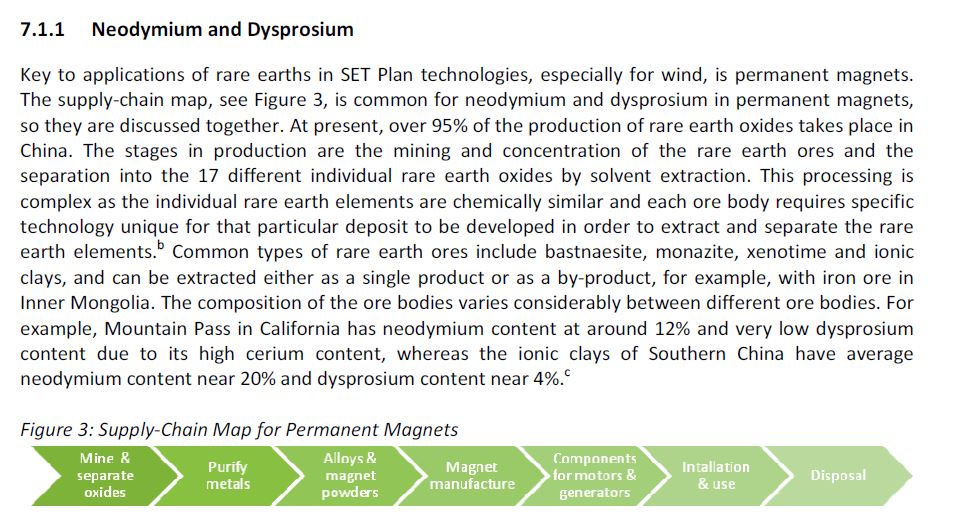

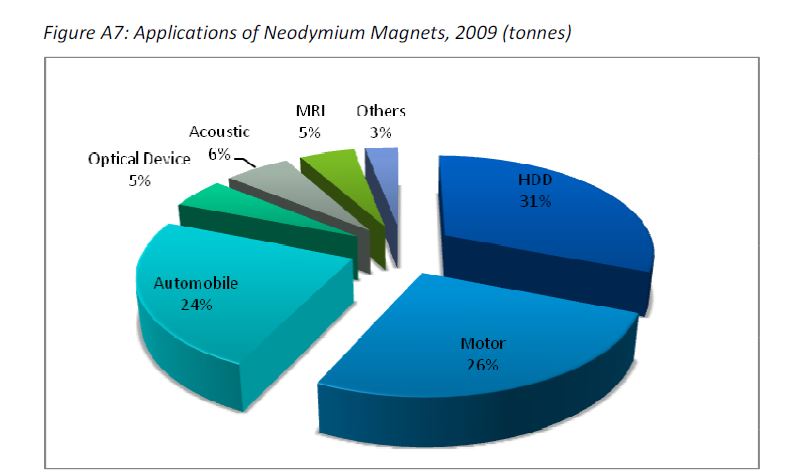

One of the more serious problems is the use of certain rare earths as the major components for magnetic motors and generators. Neodymium is a primary requirement and one of the largest usages occurs in

the Toyota Prius

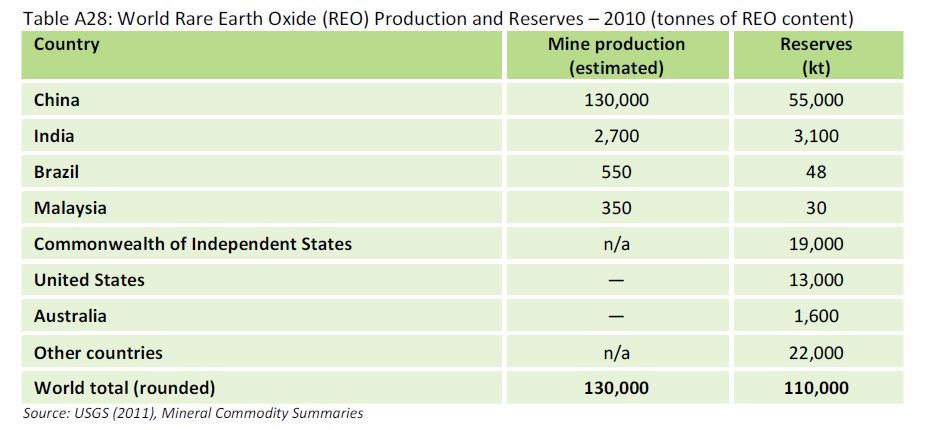

And finally, it is abundantly clear that CHINA completely controls the rare earth Market now and forever. This will undoubtedly lead to interesting political and economic dynamics in the very near future.

In sum, the lack of US access to rare earth minerals may well become the biggest obstacle to implementing large scale renewable energy sources within its boundaries. This is a serious problem. But don't believe me - here are some links to resources

that discuss this issue at some reasonable level of credibility:

|