The basic idea of stabilization is straightforward:

Choose a level defined in terms of CO2e ppm by

some year and wrap a global policy around that so as to achieve

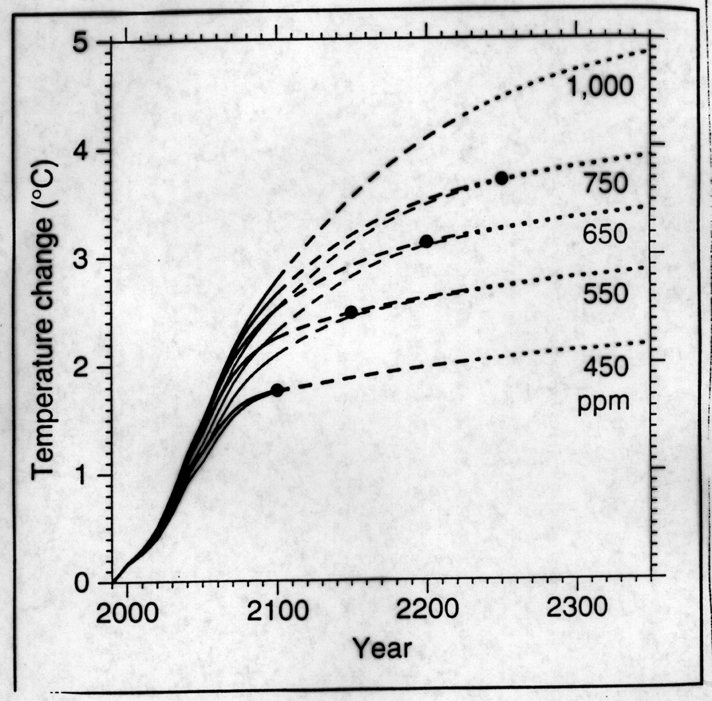

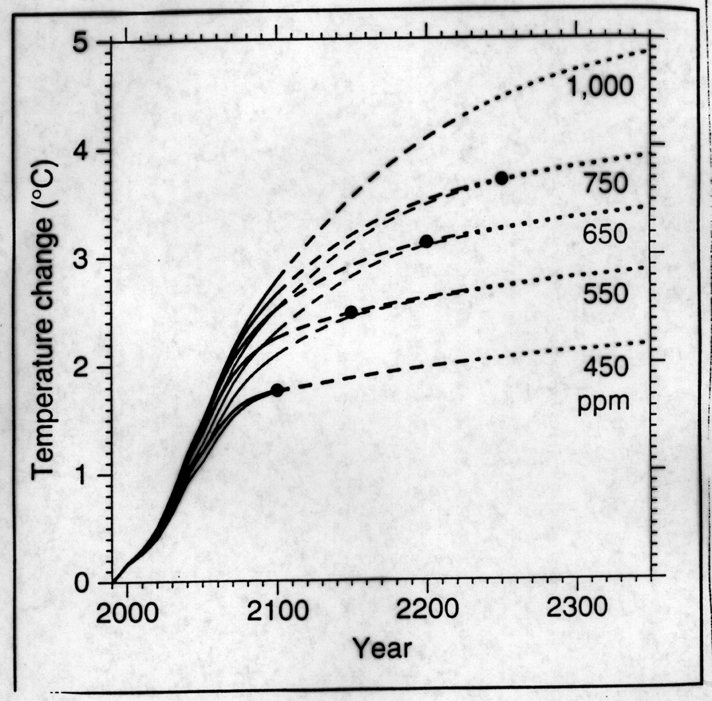

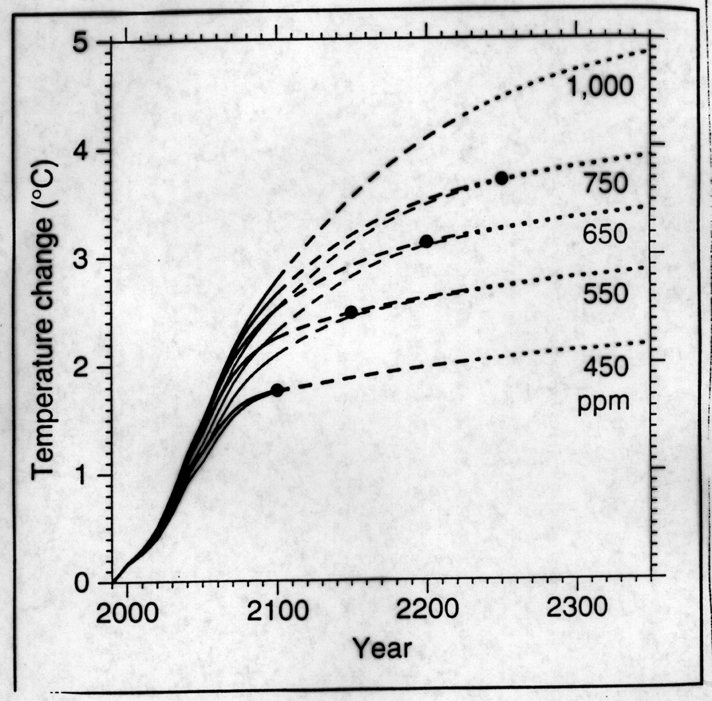

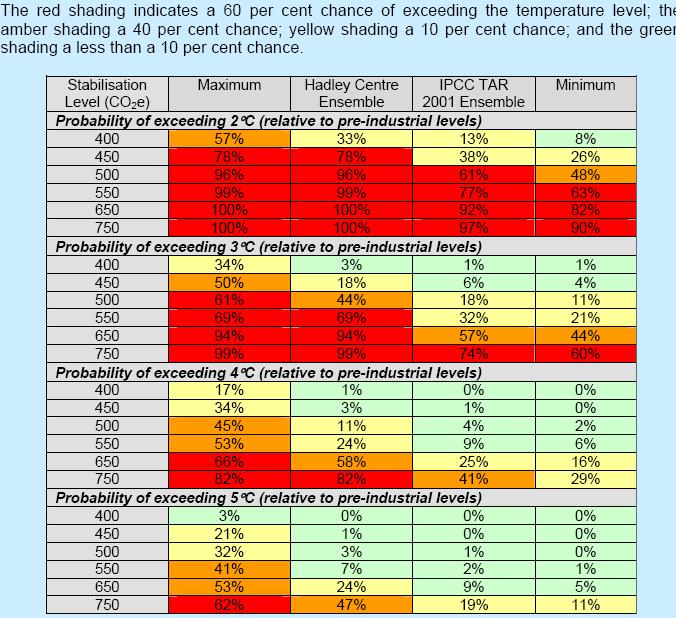

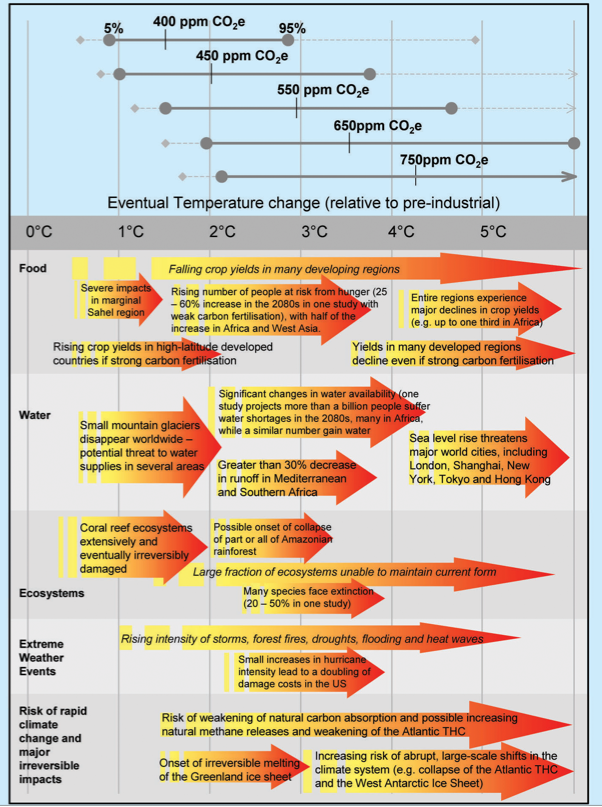

this goal. As a guide, one might consider models of predicted

temperature as a function of CO2e ppm (the e means carbon dioxide equivalent which means that methane is included). For example:

where it is clear that the range of uncertainty is large. This makes choosing a target not very easy but that's not an excuse for not doing this - nevertheless, a target remains unchosen. In addition,

given that the oceans have absorbed 80-85% of the industrial produced warming over the last 40 years, there is still "warming in the pipeline" available to the atmosphere as the ocean/atmosphere system reaches a new equilibrium. This warming is roughly equivalent to adding an extra 50-100 ppm to the atmosphere.

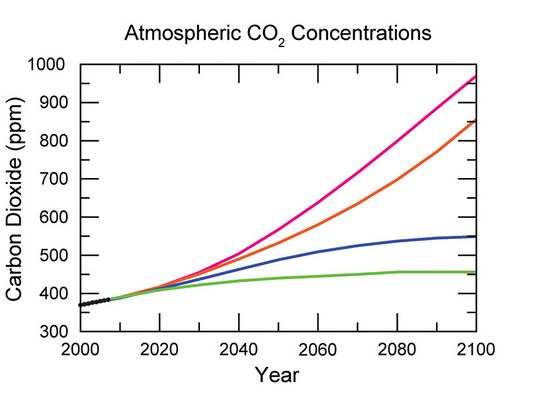

From the IPCC 2007 report there are 4 emissions scenarios shown below. Given the current levels of CO2e ppm the opportunity to be on the green line has been lost. The best that we can hope for is 550 ppm (blue line) but time is rapidly running out to meet that goal. In all likelihood we remain on one of the two indicated rising trajectories.

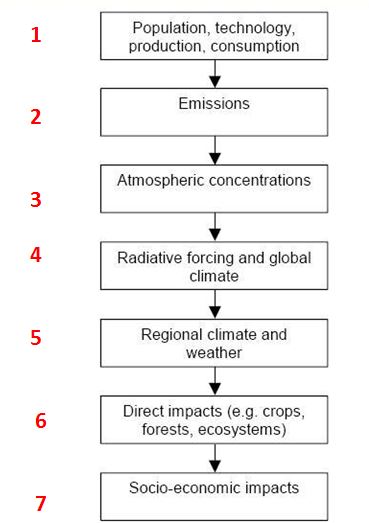

Indeed, this problem is difficult to solve because of the direct interconnectedness of climate change with economic gain when using fossil fuels. This connectedness in the chain is shown below:

Now which of these boxes to do we have any control of and what is the potential amplitude of that control. Assessing this should guide policy decisions:

- Box 1: We have very little control over any of this. History proves us. While we all like to believe that consumption patterns will change, there is no evidence that this will occur.

- Box 2: But we can control the emissions by changing out as much of the production/consumption energy chain to renewable

energies as quickly as possible. Currently this is not happening at any where near the rate of replacement needed to compensate for increasing consumption.

- Box 3: Responds directly to Box 2

- Box 4: This box pertains to model predictions and we have already seen they are very uncertain,

- Box 5: This is likely the adaptation box, we have no control over the amplitude of regional climate change.

- Box 6: Yes these are the likely direct indicators and if we can see them coming, and, more importantly, believe they will come then some advanced planning can occur. World food security is a big deal but there are not current strategies to deal with wholesale crop failure as a direct consequence of climate change.

- Box 7: This again mostly lies in the area of adaptation and not mitigation.

This mini analysis should make one thing clear. The only box under our direct control is BOX 2 and hence our planning strategies should revolve around limiting and eliminating future

sources of Carbon emission.

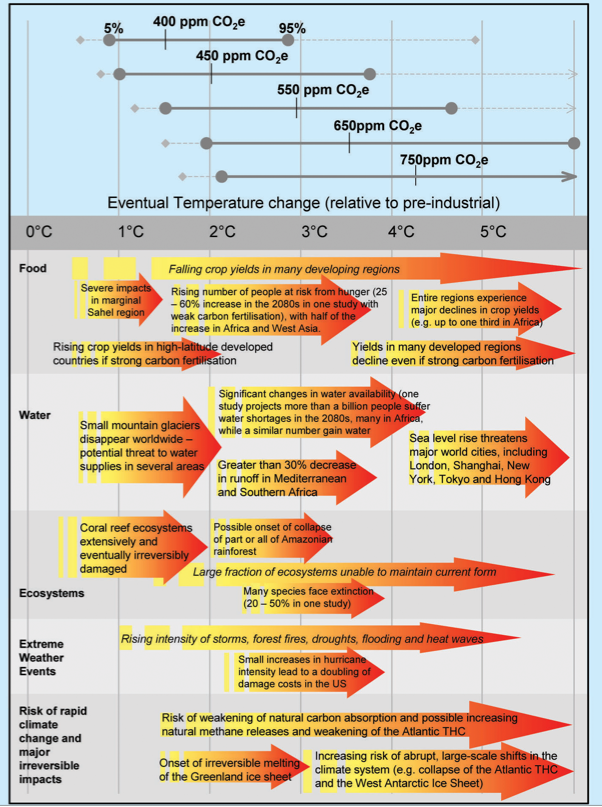

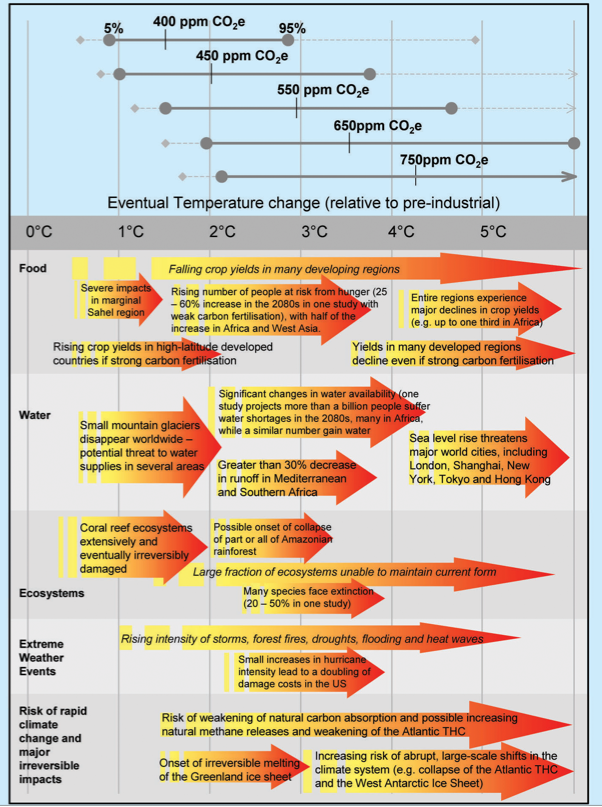

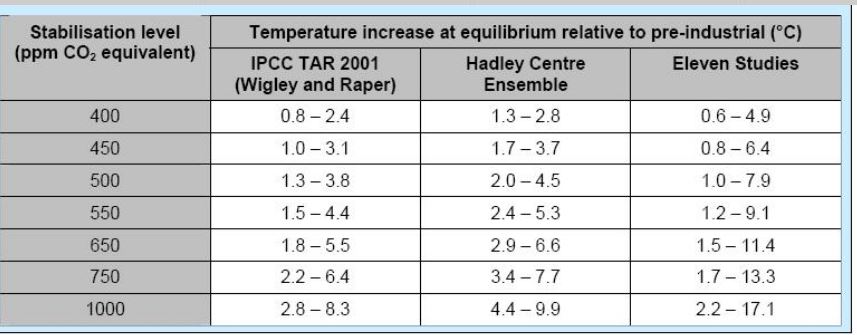

An update of the previous table shown above is here:

The World Bank report, referenced earlier is centered on avoiding

the third box and we still have opportunity to do so.

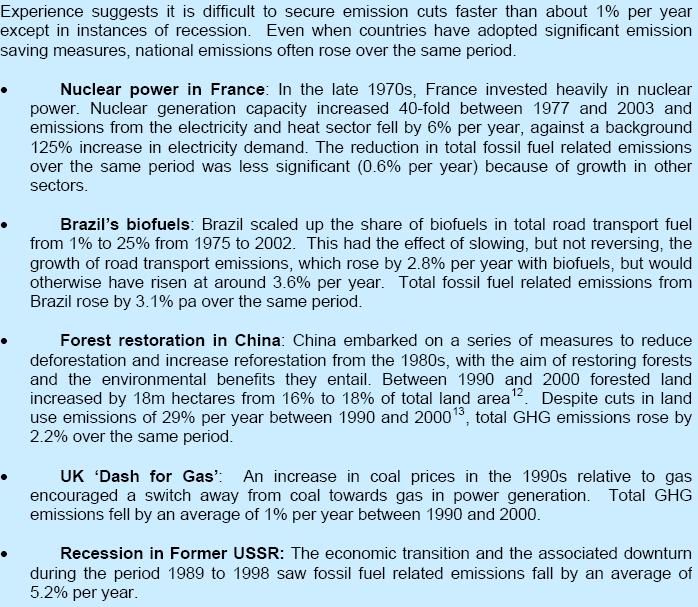

The many challenges of stabilization:

-

If carbon absorption were to weaken (because of ocean saturation previously discussed), future emissions would need to be cut

even more rapidly to hit any given stabilisation target for atmospheric concentration.

-

Energy systems are subject to very significant inertia. It is important to avoid

getting locked into long-lived high carbon technologies, and to invest early in

low carbon alternatives. We are not doing this on anywhere near the scale that

needs to be done. Remember in the US we have about 1TW of fossil based electrical nameplate power which is increasing

every year due to NG additions. We are adding wind capacity at the rate of only around 8-12,000

MW per year; solar additions are much lower.

-

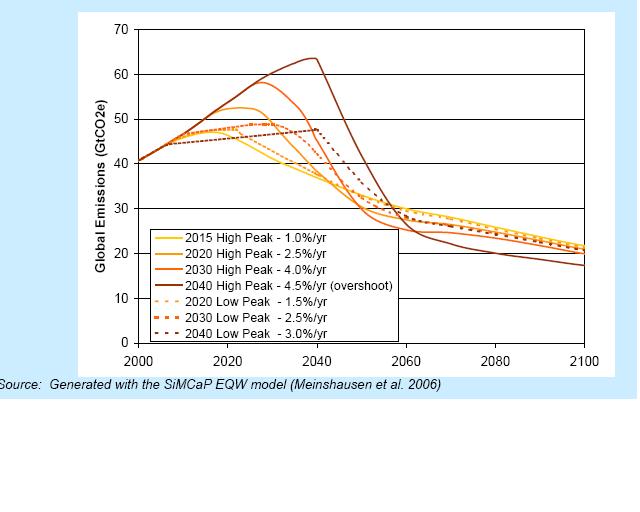

Stabilising at 550 ppm CO2e (around 440 - 500 ppm CO2 only) would require

global emissions to peak in the next 10 - 20 years, and then fall at a rate of at

least 1 - 3% per year. By 2050, global emissions would need to be around 25% below

current levels. These cuts will have to be made in the context of a world economy

in 2050 that may be three to four times larger than today: so emissions per unit

of GDP would need to be just one quarter of current levels by 2050.

-

To stabilise at 450 ppm CO2e, without overshooting, global emissions would

need to peak in the next 10 years and then fall at more than 5% per year,

reaching 70% below current levels by 2050. This is likely to be unachievable

with current and foreseeable technologies. In fact, now it does seems completely unachievable.

- Any overshoots of peak trajectories require severe post peak reductions.

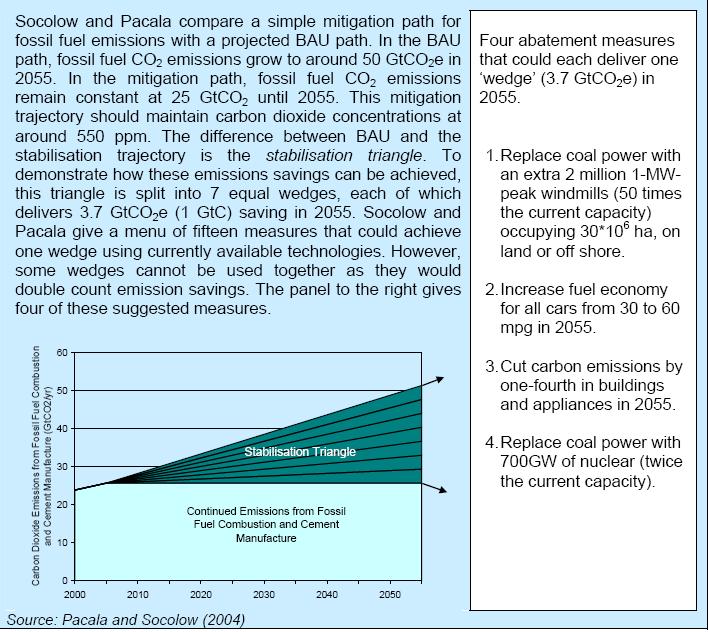

The above points are effectively summarized in the figure below:

Finally, while Carbon, Capture and Storage (CCS) is a main component of stabilization - we are again not achieving this at any relevant scale. CCS while be discussed in more detail later

in this course. Hence our future lies somewhere in this range:

|