direct regulation but difficult to verify

direct regulation but difficult to verify

more in line with the way markets

might actually work.

more in line with the way markets

might actually work.

Lets look at an example.

An industrial district has 3 electricity power plants operating in it (A, B and C). These facilities produce pollutant X as a consequence of generating electricity.

By some process, local regulators determine that a maximum of 5 units of pollutant X can go into the atmosphere for any one year from these three sources.

This then leads to the concept of emission rights. Emissions are a combination of demand, plant efficiency and source of fuel. Its the demand side of emissions that makes a direct carbon tax somewhat problematical.

Now is where a market can come into play.

Suppose that Plant A invests in new technology and becomes more efficient such that it now emits only

2 units a year to meet demand.

At the same time, Plant B receives a big order and must scale up production, causing it to increase its

output of pollutant X to 2 units. Plant A sells its spare unit to Plant B.

Nothing changes for Plant C.

In the end there are still no more than 5 units of pollutant X going into the atmosphere, but the allocation of those 5 units

has changed.

The environmentally-optimal emission level thus never gets exceeded but the market, rather than regulators,

decide on the most efficient way to divide up that limit among participating entities.

Potential pitfalls of this approach:

this may require large regional scales.

this may require large regional scales.

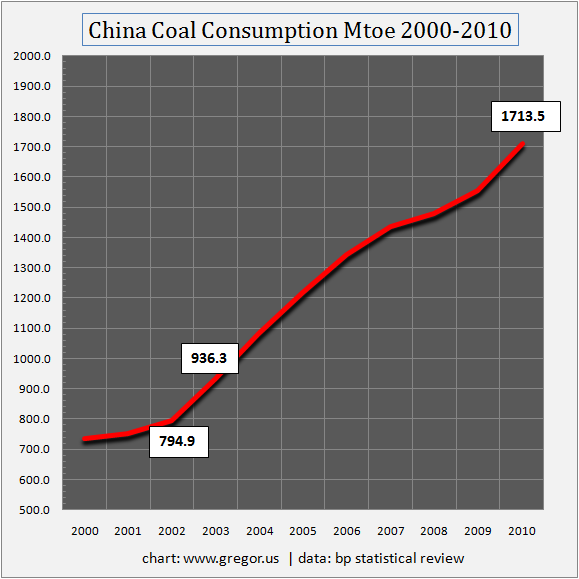

An important attribute about CO2 and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) is that they are global pollutants.

Their presence in the atmosphere in large quantities will be the same whether they came from a Chinese power plant or an American SUV.

This means that carbon accounting on a global scale may, in fact, be impossible.

What does the carbon market look like:?

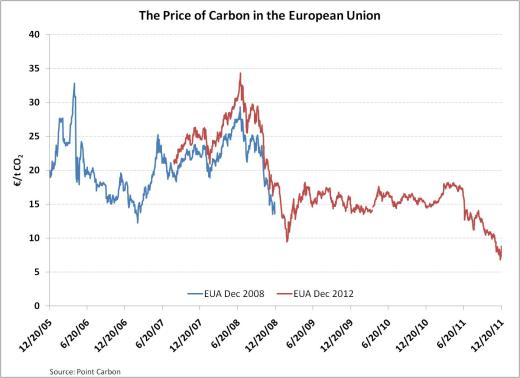

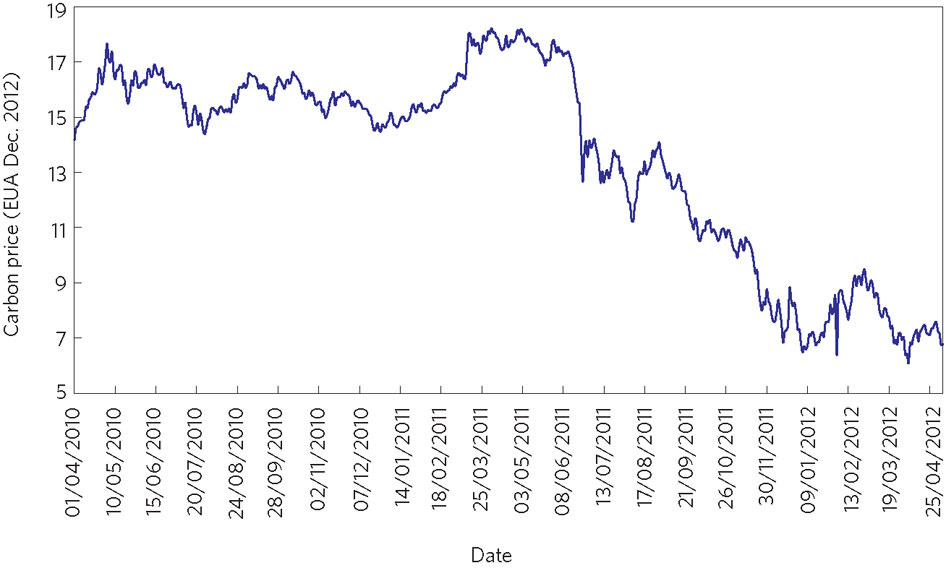

The global recession is clearly manifested, but as of today, Carbon prices continue to plummet:

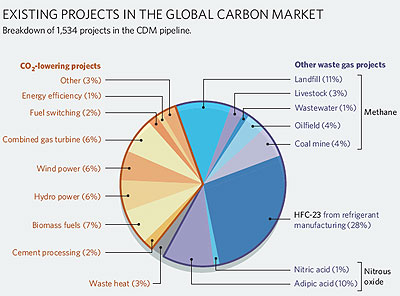

Nitrous oxides come from three principle sources:

The last three gases come from various industrial processes. In particular HFC -23 is a by product of the manufacture of refrigerant gases. It is a very potent greenhouse gas but it also costs very little for the manufacturing process to limit. Therefore, its "distorted" in the global carbon market and currently makes up about 30% of the available CDM credits.

In other words, for a very small investment on the part of the manufacturing industry, they potentially get a large slice of the CDM/carbon market pie. This removes the incentive to do much about Carbon Dioxide!

Secondarily, the largest share of the carbon market pie can be obtained by better management of landfill emissions.

Hence, the main target, the release of carbon associated with electricity generation, remains untouched by the current CDM process.

This must change and the focus must be solely on CO2.