The Post World War 2 vision for science in America.

We can start this disussion with Vannevar Bush and his driving vision for the NSF. This is the source document and also contains letters between Bush and President Roosevelt

While formulating his overall vision vision he writes two important things:

- Basic research is performed without thought of practical ends.

- One of the peculiarities of basic science is the variety of paths which lead to productive advance. Many of the most important discoveries have come as a result of experiments undertaken with very different purposes in mind. Statistically it is certain that important and highly useful discoveries will result from some fraction of the undertakings in basic science; but the results of any one particular investigation cannot be predicted with accuracy

Taken together these statements, along with the rest of his vision strongly argues that the Nation (and Bush does become Nationalistic in his vision) needs to invest in scientific curiosity and for the first few post WW2 decades, this is essentially what happened. Bush's basic arguments:

Need for Post WW II investment

Government had important role to play in fostering creation of new knowledge and in training individuals to create that knowledge

Ultimately this leads to the formation of the NSF

Thought universities were right place because they were "least under pressure for immediate, tangible results."

Early on in our more enlightened pathway to scientific funding in the US, the Oct 4, 1957 sputnik launch caused a massive over-reaction and likely completely changed our funding strategies. This is largely because the enemy had reached space first with a 200 lb beach ball size thing that orbited for 98 minutes. An accurate succinct history of this can be found here: https://history.nasa.gov/sputnik/ and its not an accident that the "textbook" for this class is starts out with the words: Beyond Sputnk ...

To many, the Sputnik launched signaled that America was not technically superior in the world and this caused a wide spread change. NASA was quickly established (like 6 months later) and the US DoD put lots of government resources into the Explorer project whose first launch was Jan 31, 1958 (just 4 months after the enemy launch) and that launch discovered the magnetic radiation belts around the earth. This fundamental discovery (which also helps explain why life can exist on the surface of a planet that is subject to large energetic ion flux) was an accidental by product of the ensuing arms race started by Sputnik.

In this context, Ryber 2003 writes about the moral obligation of scientists . Most scientists don't feel like they have one.

More specifically, Ryberg raises the following issues that scientists usually use to absolve themselves of any responsibility for the possible repercussions of their research:

In short, since the essential nature of inquiry is that one cannot foresee what one will discover, the scientist cannot properly be held responsible for the results that follow from his research.

The Scientists-do-not-decide-on-application Argument --

More plainly put, the argument says that 'if I did not do it, someone else would" therefore "I did not really do anything wrong".

The Cog in the Chain Argument

If the work of a scientist who contributes to military research is a necessary condition for the final application of, say, a certain weapon system or some other piece of military technology, then the fact that the scientist is far distant from the application of the weapon system, in the sense that many others' work and decisions are also necessary for the application, does not reduce the responsibility of the scientist.

In sum, Ryberg dismisses all of these arguments and asserts that scientists are obligated to engage in unintended consequences thinking. That is the kind of thinking that is necessary for science to become interested in policy

The current situation in broadbrush.

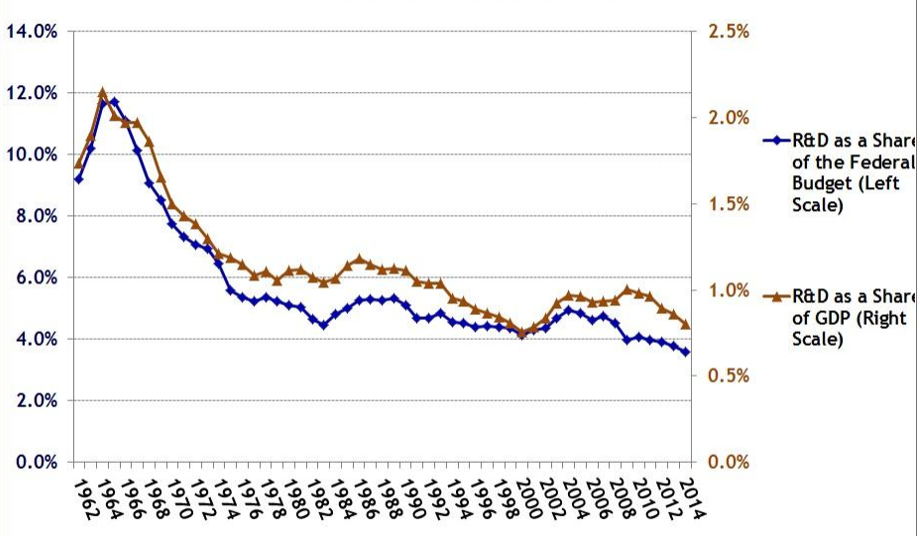

In May 2013 I was asked by the National Science Board to do an audit and make a presentation about the evolution of science funding over the previous 20 years. I talked about that the Nation was no longer honoring the Vannevar Bush's vision in terms of how science is being funded. The argument in brief was based on dividing science funding into 4 areas:

- New Facilities

- Legacy Facilities (large DOE national labs)

- Individual PI Grants (see the rant below related to KDI on consortium funding)

- Graduate Student Training (i.e. future science successes for the US).

These 4 areas are being supported basically on a flat dollar budget over this 20 year period with the following consequences

- Inflation associated with building new facilities is 8-12% a year

- Labor costs associated with Legacy Facilities have increased about 5-7% a years (largely due to rising health care costs).

- As a result of 1 & 2: Individual PI grants are very squeezed (this is also due to consortium granting priority) which greatly impacts the training of our future scientists. That's what we have sacrificed by having a flat budget (see also below). The National Science Board did pay attention to that, but of course, nothing on a significant scale has happened.

The bottoms line is that data clearly shows we are no longer honoring the early vision of

The flow of scientific knowledge must be both continuous and substantial

Currently, the substantial part is now meaning better use of science and data to make more effective public policy.

Science Funding:

Below we see that once upon reasonable funding for sciences had a period of about 20 years (1960-1980) – since then funding is mostly flat, even the size of the scientific community has grown significantly. We are not scaling.

The basic reason behind this decline is that science funding now appears to be less relevant than other kinds of investments. Having science better interface with policy might be the best way for science to appear, again, to be relevant to Congress.

|