A few points from the text:

Many surveys consistently show that the Public doesn't necessarily need to understand science, to support it. Now this is a bit backwards, if scientists are under the perception that public support will increase if the public BETTER understands science. The data don't support this perception.

My intepretation of this is simply that the public conflates science with both a) technology (as previously discussed) and b) improvements in medical science.

1997 Quote in a panel on the Media and the 40th year since Sputnik

Well constructed science literacy tests can be quite insightful

Here is one example But you do need to be careful on how you construct these questions so the answer is not obvious (often via elimination of choices). The example (2015) test/survey contains both good and not so good questions.

A conundrum: The Value of Knowledge

If the sticker shock is too high (e.g. SSC) then there is a price on the value of knowledge and this is generally not recognized by

the science community:

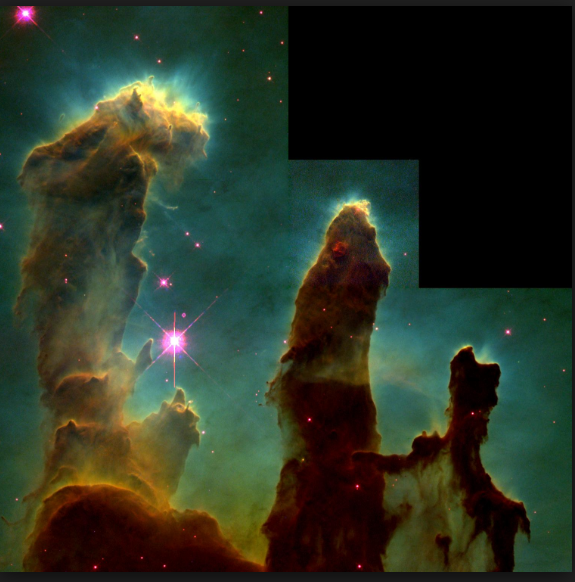

Now concernig the SSC (the text characterizes this saga well at the start of Chapter 12; Homer Neal was very involved in this at the time - also remember that the Hubble Space Telescope was launched broken in 1990 - so can America do big science projects at all?) This from 1992

So if a large scale scientific instrument is deemed to be a niche-only instrument, then this will likely cause problems. HST, however, was going to do high resolution imaging in space which had never been done before and of course would be cool because now I could have a background on my desktop.

The effectivness of very large science projects, most of which are internationally in nature, remains unclear. Although the discovery of the Higgs maybe a good example of something that had public value as a story, it is unclear in general of the overall scientific and public value of these kinds of enterprises given the enormous resources required to make them. (note the book was written well before the Higgs was discovered).

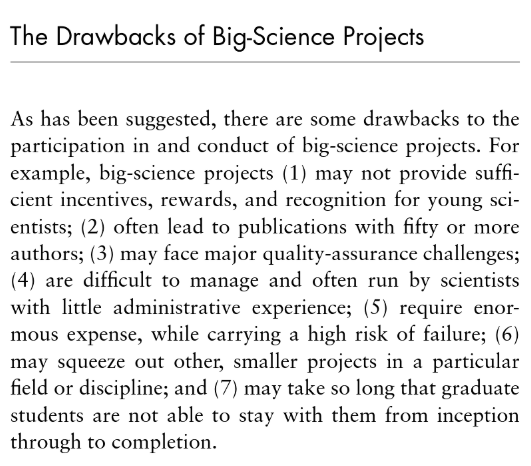

The text does a nice job of summarize some of the potential drawbacks of these kinds of projects and this summary will form the basis for a class discussion topic for next week.

Quick summary of these 7 points:

- some truth to this, and is an unintended consequence, as the system now rewards legacy (those with the most experience are larger parts of the project). This means preferential access (for GDB: HST, Spitzer). Big science may be biased against young investigators.

Note: IRAS (Infrared Astronomical Satellite) was launched in Jan 1993 as a survey only instrument with no proprietary claim to the data has produced the largest number of papers compared to anyother single astronomical instrument (and yes this includes HST).

- No shit!

- While there is a lack of comprehensive oversight and a lot of blame storming (GDB was involved in the spherical aberration blamestorm for HST; sign error in grinding machine).

- Not really a very big problem

- Yes!

- This is the discussion question to be had later

- Yes there is some truth that graduate PHD thesis that are involved with some aspect of the big instrument are delayed

Overall summary on the public and scientists:

In general, scientists, graduate student TAs, science instructors, etc need to become much more aware of the general biases that students/the public have on various issues that relates to their own personal background driven by a)the belief system of their parents, b) misconceptions obtained in K12 (i.e. the greenhouse effect as a blanket on the earth - not very scientifically accurate), c) religous, moral, and ethical views (GMOs are a good example: feed an overcrowded world or not?) What scientists are not good at is presenting the big picture that each choice is embedded in in a way that helps students and the public understand what the big picture is.

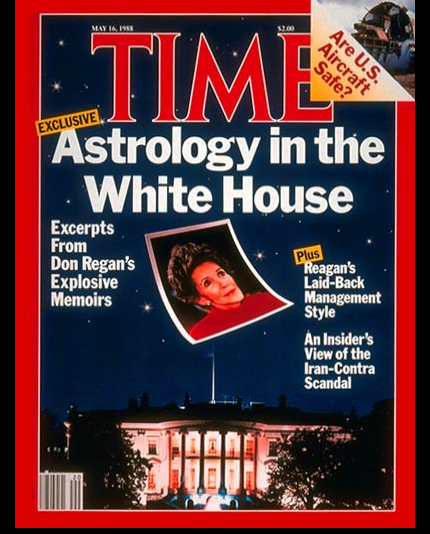

Then, of course, there is this:

Time Magazine Cover May 1988

From Scientific American

|