All about Jupiter

Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

Mass (kg)........................................... 1.90 x 10^27

Diameter (km)....................................... 142,800

Mean density (g/cm^3) .............................. 1.314

Escape velocity (m/sec)............................. 59500

Average distance from Sun (AU)...................... 5.203

Rotation period (length of day in Earth hours)...... 9.8

Revolution period (length of year) (in Earth years). 11.86

Obliquity (tilt of axis) (degrees).................. 3.08

Orbit inclination (degrees)......................... 1.3

Orbit eccentricity.................................. 0.048

Mean surface temperature (K)........................ 120 (cloud tops)

Visual geometric albedo............................. 0.44

Atmospheric components.............................. 90% hydrogen,

10% helium,

.07% methane

Rings............................................... Faint ring.

Infrared spectra imply dark rock fragments.

Basic Properties:

Jupiter is the largest of the eight planets, more than 10 times the diameter of Earth and more than

300 times its mass. In fact, the mass of Jupiter is almost 2.5 times that of all the other planets

combined. Being composed largely of the light elements hydrogen and helium, its mean density is

only 1.314 times that of water. The mean density of Earth is 5.5 times that of water. The pull of

gravity on Jupiter at the top of the clouds at the equator is 2.4 times as great as gravity's pull at

the surface of Earth at the equator. The bulk of Jupiter rotates once in 9 hours, 55.5 minutes,

although the period determined by watching cloud features differs by up to five minutes due to

intrinsic cloud motions.

The visible surface of Jupiter is a deck of clouds of ammonia crystals, the tops of which occur at a

level where the pressure is about half that at Earth's surface. The bulk of the atmosphere is made

up of 89% molecular hydrogen (H2) and 11% helium (He). There are small amounts

of gaseous ammonia (NH3), methane (CH4), water (H2O),

ethane (C2H6), acetylene (C2H2), carbon monoxide

(CO), hydrogen cyanide (HCN), and even more exotic compounds such as phosphine (PH3) and

germane (GeH4). At levels below the deck of ammonia clouds, there are believed to be ammonium

hydro-sulfide (NH4SH) clouds and water crystal (H2O) clouds, followed by clouds of liquid water.

The visible clouds of Jupiter are very colorful. The cause of these colors is not yet known.

Contamination by various polymers of sulfur (S3, S4, S5, and

S8), which are yellow, red, and brown,

has been suggested as a possible cause of the riot of color; but, in fact, sulfur has not yet been

detected spectroscopically, and there are many other candidates as the source of the coloring.

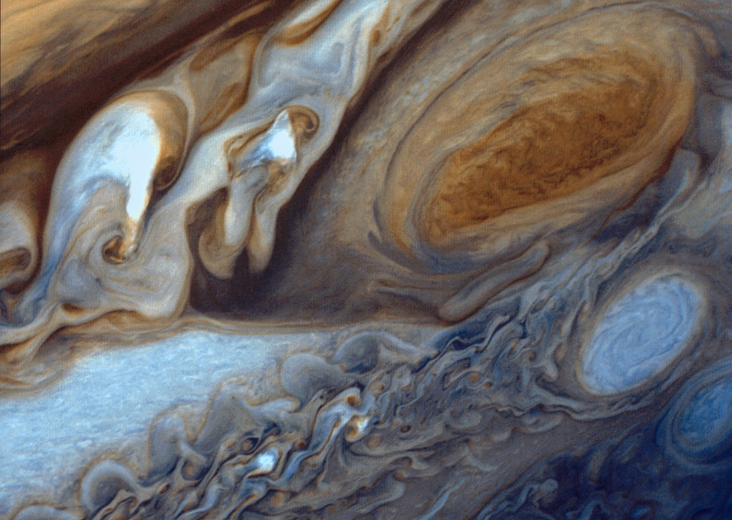

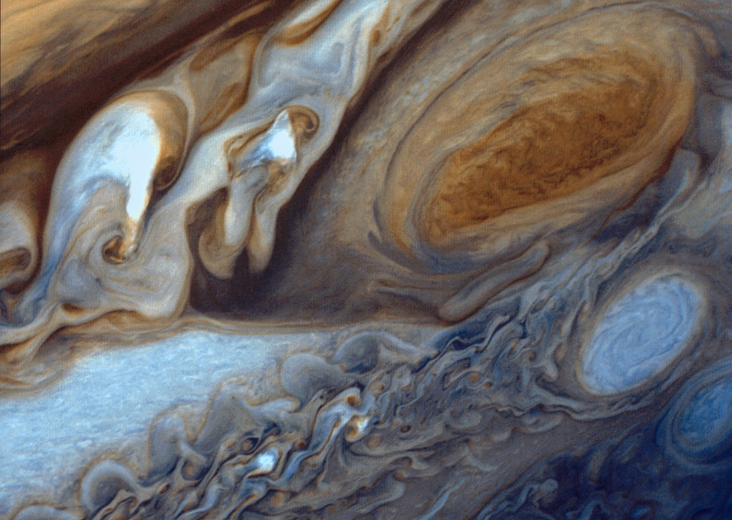

Great Red Spot (NASA/JPL)

The exterior of Jupiter is noted by its brightly colored latitudinal

zones, dark belts and thin bands dotted with numerous storms and eddies.

Due to differential rotation, the equatorial zones and belts rotate faster

than the higher latitudes and poles.

The meteorology of Jupiter is very complex and not well understood. Even in small telescopes, a

series of parallel light bands called zones and darker bands called belts is quite obvious. The polar

regions of the planet are dark. Also present are light and dark ovals, the most famous of these

being the Great Red Spot. The Great Red Spot is larger than Earth, and although its color has

brightened and faded, the spot has persisted for at least 162.5 years, with the earliest definite

drawing of it done by Schwabe on September 5, 1831. (There is less positive evidence that Hooke

observed it as early as 1664.) It is thought that the brighter zones are cloud-covered regions of

upward moving atmosphere, while the belts are the regions of descending gases, the circulation

driven by interior heat. The spots are thought to be large-scale vortices, much larger and far more

permanent than any terrestrial weather system.

Credit: University of Arizona

Jupiter movie

The zones and belts are zonal jet streams moving with velocities up to

400 miles/hr. Wind direction alternates between adjacent zones and

belts. The light colored zones are regions of upward moving convective

currents. The darker belts are made of downward sinking material. The

two are therefore always found next to each other. The boundaries of the

zones and belts (called bands) display complex turbulence and vortex

phenomenon.

Note: Upward moving gases in Jupiter's atmosphere bring white clouds of

ammonia/water ice from lower layers. Downward moving gases sink and allow

us to view the top, darker layers.

The detailed

structure in Jupiter's atmosphere is

dominated by physics known as fluid dynamics. Note that the atmosphere of

Jupiter so dense and cold that it behaves as a fluid rather than a gas.

At the point were we see features the atmosphere pressure is 5 to 10 times

that of the Earth's atmospheric pressure. The simplest theories in fluid

dynamics predict two types of patterns. One pattern occurs when a fluid

slips by a second fluid of a different density. Such an event is known as

a viscous flow and produces wave-like features at the boundary of the two

fluids. A second pattern is produced by a stream of fluid in a constant

medium. The stream breaks up into individual elements. These smaller

sections can develop into cyclones.

Cyclones develop due to the Coriolis effect where the lower latitudes travel

faster than the higher latitudes producing a net spin on a pressure

zone. The cyclones on Jupiter are regions of local high or low pressure

spun in such a fashion. Note that the direction of the spin differs

in the two hemispheres where counter-clockwise spin is in the North and

clockwise spin is in the South.

Brown ovals are low pressure cyclones/storms in the North. White ovals

are high pressure cyclones/storms in the South. Both can last on the

order of tens of years.

The energy needed to power all the turbulence in Jupiter's atmosphere

comes from heat released from the planet's core.

The most obvious feature on Jupiter is the Great Red Spot

Redspot movie

Gas planets do not have solid surfaces, but rather build-up in pressure

and density as one goes deeper towards the core. Different colors

represent different depths into Jupiter's atmosphere. The colors (reds,

browns, yellows, oranges) are due to subtle chemical reactions involving

sulfur. Whites and blues are due to CO2 and H2O ices.

The interior of Jupiter is totally unlike that of Earth. Earth has a solid crust floating on a denser

mantle that is fluid on top and solid beneath, underlain by a fluid outer core that extends out to

about half of Earth's radius and a solid inner core of about 1,220-kilometer (758-mile) radius. The

core is probably 75 percent iron, with the remainder nickel, perhaps silicon, and many different

metals in small amounts. Jupiter, on the other hand, may well be fluid throughout, although it

could have a small solid core (say up to 15 times the mass of Earth!) of heavier elements such as

iron and silicon extending out to perhaps 15% of its radius. The bulk of Jupiter is fluid hydrogen in

two forms or phases, liquid molecular hydrogen on top and liquid metallic hydrogen below; the

latter phase exists where the pressure is high enough, say 3-4 million atmospheres. There could be

a small layer of liquid helium below the hydrogen, separated out gravitationally, and there is

clearly some helium mixed in with the hydrogen. The hydrogen is convecting heat (transporting

heat by mass motion) from the interior, and that heat is easily detected by infrared measurements,

since Jupiter radiates twice as much heat as it receives from the Sun. The heat is generated largely

by gravitational contraction and perhaps by gravitational separation of helium and other heavier

elements from hydrogen, in other words, by the conversion of gravitational potential energy to

thermal energy. The moving metallic hydrogen in the interior is believed to be the source of

Jupiter's strong magnetic field.

Comparison of all gas giants

(Lunar and Planetary Institute)

Jupiter's magnetic field is much stronger than that of Earth. It is tipped about 11° to Jupiter's axis

of rotation, similar to Earth's, but it is also offset from the center of Jupiter by about 10,000

kilometers (6,200 miles). The magnetosphere of charged particles which it affects extends from 3.5

million to 7 million kilometers (2.2 to 4.3 million miles) in the direction toward the Sun, depending

upon solar wind conditions, and at least 10 times that far in the anti-Sun direction. The plasma

trapped in this rotating, wobbling magnetosphere emits radio frequency radiation measurable

from Earth at wavelengths from 1 meter (3 feet) or less to as much as 30 kilometers (19 miles). The

shorter waves are more or less continuously emitted, while at longer wavelengths the radiation is

quite sporadic. Scientists will carefully monitor the Jovian magnetosphere to note the effect of the

intrusion of large amounts of cometary dust into the Jovian magnetosphere.

The two Voyager spacecraft discovered that Jupiter has faint dust rings extending out to about

53,000 kilometers (33,000 miles) above the atmosphere. The brightest ring is the outermost, having

only about 800-kilometer (500-mile) width. Next inside comes a fainter ring about 5,000

kilometers (3,100 miles) wide, while very tenuous dust extends down to the atmosphere.

The innermost of the four large satellites of Jupiter, Io, has numerous large volcanoes that emit

sulfur and sulfur dioxide. Most of the material emitted falls back onto the surface, but a small part

of it escapes the satellite. In space, this material is rapidly dissociated (broken into its atomic

constituents) and ionized (stripped of one or more electrons). Once it becomes charged, the

material is trapped by Jupiter's magnetic field and forms a torus (donut shape) completely around

Jupiter in Io's orbit. Accompanying the volcanic sulfur and oxygen are many sodium ions (and

perhaps some of the sulfur and oxygen as well) that have been sputtered (knocked off the surface)

from Io by high energy electrons in Jupiter's magnetosphere. The torus also contains protons

(ionized hydrogen) and electrons. It will be fascinating to see what the effects are when large

amounts of fine particulates collide with the torus.

Movie of Jupiter's Magnetic Field

Movie of Jupiter's Magnetic Field

Formation of Jupiter

The formation of Jupiter (and the other Jovian worlds) starts with the

accretion (build-up) of ice-covered dust in the outer, cold solar

nebula

Note that, due to gravity, the heavier elements sink to the core of

proto-Jupiter, and the lighter elements (H and He) remain in the

atmosphere.

The formation of Jupiter (and to some extent Saturn) has recently come

under scrutiny as some pieces don't entirely fit convenient theory any more.

There are two basic possible formation histories:

- Standard One: Acretion of Icy Material onto a rocky core.

- A new model: Disk Instability.

- While this model is technically difficult to explain at this level, the bottom line is that it suggests that Jupiter forms mostly as a whole object and not by accretion.

- This model is consistent with its large mass and indeed in the theory, only objects with masses greater than 50 earth masses could form in this way.

- This model also explains other features of the solar system. For instance, its hard to understand why we have an asteroid belt if Jupiter grows slowly via acretion.

- The model suggests that Jupiter formation via disk instability can take as little as one million years.

- The main problem with this model is that is not a "natural" way to make planets

but it appears to be ubiqitous as there are plenty of extra solar planets discovered with Jupiter masses.

but it appears to be ubiqitous as there are plenty of extra solar planets discovered with Jupiter masses.